REFLECTIONS ON ORSON WELLES, PT. III: THE LADY FROM SHANGHAI

THE BACKGROUND

Orson Welles came to make his penultimate Hollywood film in September 1946. He had finished work on The Stranger nine months previously, and had nearly bankrupted himself over the summer producing a touring theatrical adaptation of Around the World in 80 Days. He was desperate to work profitably again. The notoriously monstrous head of Columbia Pictures, Harry Cohn, invited Welles to make a film at his studio. After considering several projects which he had developed with the producer Alexander Korda, Welles decided to adapt the 1938 pulp novel If I Die Before I Wake, by R. Sherwood King. Welles had acquired the rights to the book in 1945 on the suggestion of his friend William Castle, and had the rights reassigned to Columbia, which then slowly developed the project for over a year.(1) Initially conceived as a quick B thriller, Welles soon found himself, at Cohn’s request, reshaping the material into a solid A picture starring his estranged wife, Rita Hayworth. Like The Magnificent Ambersons and The Stranger, Welles didn’t have final cut over the film. The final script had as many as four writers, although Welles was the only one to receive credit. With a 65-day schedule spread out over 12 weeks and a $2.3 million budget set, Welles began shooting on October 2nd, 1946.

The production was rife with problems from the get-go. Despite the renewed bond that Welles and Hayworth created from working together, every other circumstance surrounding filming portended the project to be doomed to failure. The weather during location filming in Mexico and California was wretched, and various cast members became terribly ill, holding up production. Additionally, Cohn continually demanded that Welles shoot more close-ups of Hayworth, for fear that Welles wouldn’t use his star to her sexiest potential. He also forced Welles to film sequences that cost extra time and money, much to Welles’s chagrin. The most explicit of these was a scene of Hayworth lying on the deck of her husband’s (Everett Sloane) yacht, singing a ballad called “Please Don’t Kiss Me.”(2) To add to the turmoil, the original cinematographer, Charles Lawton Jr., exited the production at the late stages, and Rudolph Mate (Carl Dreyer’s cinematographer) was brought in to finish the shoot (although this may have been quite welcome to Welles, since Lawton worked slowly).(3) By the time principal photography wrapped at the end of February 1947, the budget hovered just below $2.8 million, with an additional 32 days of shooting having been used.

The next few months saw Welles being subjected to a scenario with which he was all-too familiar by this point in his career: studio tampering. Cohn still wanted more close-ups, so he had Welles shoot them in the studio against a process screen, making Welles’s tightly constructed sequences even more disjointed. Parts of scenes were re-dubbed, which created an incongruity of dubbed and direct sound being juxtaposed within the same scene. Welles begrudgingly agreed to all of these requests. But the most egregious of all of Cohn’s meddling was during the editing of the film.

According to Welles’s cutting continuity, dated January 1947, the film was 155 minutes long. Sixty-nine minutes were then cut, leaving the existing version at 86 minutes. Cohn and his editor, Viola Lawrence, gutted numerous sequences throughout the film in order to pare down the length. After an unsuccessful test screening in Santa Barbara, Lawrence cut the movie even more, eventually making much of the plot incomprehensible. Welles and his friend Charles Lederer then wrote a voice-over narration to help clarify narrative points lost in the muddle, much to Welles’s chagrin.(4)

James Naremore cites not only the film’s most famous sequence–the Crazy House/Hall of Mirrors climax–as one of those most tragically gutted, but also the opening sequence when Michael O’Hara (Welles) and Elsa Bannister (Hayworth) meet. The sequence would have begun with heavy cross-cutting, establishing the main players, and why many of them–Broome (Ted de Corsia), and Grisby (Glenn Anders) in particular–are in Central Park when Elsa is trying to get back to her car. After this cross-cutting, a long tracking shot would have followed Elsa’s carriage riding through the park, then to Michael walking, then to a police car driving (Jonathan Rosenbaum compares it to the opening shot of Touch of Evil). The dialogue between Michael and Elsa after he rescues her from being mugged was also more substantial, with a suggestive reference to Don Quixote; interestingly, Cohn had Lawrence cut all dialogue pertaining to literature or the characters’ fascinations with books.

Sadly, Welles had to swallow all of these changes. He did not have final cut, nor did he have the clout among Columbia executives to prevent these changes. He wrote a lengthy memo to Cohn protesting many alterations, but it was too little, too late. He was most furious with the score by Columbia composer Heinz Roemheld. Welles had very specific ideas for the music, and believed Roemheld discarded all of the irony, satire, and bite that Welles had planned; in its place, melodrama and corny romanticism filled the soundtrack. He was especially annoyed with the turning of “Please Don’t Kiss Me” into a theme that ends up recurring throughout the entire film. One scene in particular sparked Welles’s ire:

"...There is nothing in the fact of Rita’s diving to warrant a big orchestral crescendo...What does matter is Rita’s beauty...the evil overtones suggested by Grisby’s character, and Michael’s bewilderment. Any or all of these items might have inspired the music. Instead, the dive is treated as though it were a major climax or some antic moment in a Silly Symphony; a pratfall by Pluto the Pup, or a wild jump into space by Donald Duck." (Orson Welles & Peter Bogdanovich, This is Orson Welles, ed. Jonathan Rosenbaum, 1992, p. 195)

The terrible score, along with the cutting of the Crazy House/Hall of Mirrors sequence, were the problems about which Welles would talk most over the next several decades. Welles’s friend and one of Shanghai’s associate producers, Richard Wilson, even said one of his greatest professional regrets was not saving Welles’s first cut of the Crazy House sequence. Inexplicably, Cohn held up the release of The Lady from Shanghai for a year. By the time it was released in May 1948, Welles had shot Macbeth at Republic Studios in just three weeks, and then had decamped for Europe, destined to become financially what he had always been artistically: independent.(5)

THE REVIEW

Unlike The Stranger, which does require one to wonder what might have been, there is more than enough of Welles’s madness in The Lady from Shanghai to marvel at its wicked glee, acidic satire and weary romanticism. Welles allegedly screened The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari for the cast and crew before production began, and its shadow haunts the many baroque set pieces within Welles’s film.

What is striking about The Lady from Shanghai, for better and for worse, is the film’s juxtaposition of tones. From the first sweaty, swooping crane shot descending into the sailor’s hiring hall, where we see rich attorney Arthur Bannister (Everett Sloane) ask Michael O’Hara (Welles) to captain his yacht, to the legendary shoot-out in the Hall of Mirrors at a San Francisco amusement park, the film is filled with wickedly baroque, grotesque images and characters. Bannister’s crippled attorney, the drunk madman Grisby (Glenn Anders), and the smart-aleck detective Broome (Ted de Corsia) all border on the demented, sick characters born of a sick culture that believes human beings are its playthings. Welles’s camera shoots warped close-ups and highly suggestive tableaux to evoke the nightmarish world into which O’Hara has entered. Even Hayworth is otherworldly. On the surface of things, this only makes sense, as her hair is short and blonde. But it is something else. She is cold, distant, all interior, as opposed to her vibrantly sexual persona. Elsa is both innocent and vicious, and when she begins to speak in Chinese while pursuing Michael toward the climax of the film, one realizes that this is a fiercely intelligent woman whose past is far deeper than one may have anticipated.

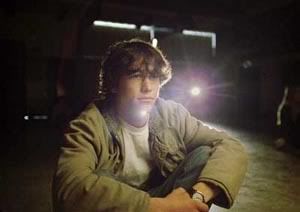

Blended with this acidic, nightmarish tone is a remarkably romantic, dreamlike one. This comes not only from Harry Cohn’s butchering of Welles’s original vision, but also from the character of Michael O’Hara himself, and Welles’s portrayal of him. Welles has never looked so gentle onscreen. (This was his only makeup-free role in his own narrative films, aside from young Charles Foster Kane.) Michael lives in a daze, unable to make either heads or tails of the people with whom he’s faced, or the situation in which he finds himself. (Indeed, this bewilderment, one could suggest, is even enhanced by Cohn’s hatchet job, as the narrative becomes unclear to the spectator as well as Michael.) He’s gentle, poetic, and deeply romantic. Michael is Welles’s only foray into a role that could be described as a dashing leading man.

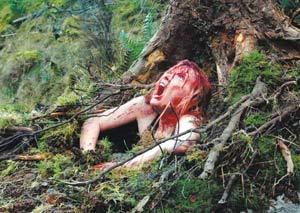

This blending of tones and styles qualifies the film to be considered of the film noir genre, but Welles’s vision of noir is decidedly different from that of Wilder, Tourneur, Lang, Preminger, Siodmak, Fuller, Ray or Kubrick. The satirical quality of the scenes with Bannister and Grisby indict modern society in a way that the aforementioned directors do not. Satire even explodes into absurd farce in the courtroom scene after Michael has been framed for Grisby’s murder. The judge isn’t aware of courtroom etiquette, Bannister and the prosecutor just yell at each other, and the jury members giggle and loudly blow their noses. Justice isn’t likely to be served to Michael. Elsa is also not a simple femme fatale, a la Phyllis Dietrichson or Brigid O’Shaughnessy. Hayworth’s performance as she lays on the floor of the Crazy House, dying, actually reminds me of the women of Sam Fuller’s films. These women are intelligent, tenacious, and not merely vicious or gentle. There is something about Elsa that makes her murderous tendencies and her romantic innocence synthetic, rather than dichotomous. As James Naremore and others have suggested, Welles has deconstructed Hayworth, exposed the audience’s sexual voyeurism, and endowed her with the intelligence she claimed he knew she had.

As much as there is to enjoy within the film, much of it feels awkward. The dubbed lines, the abrupt close-ups, and the process screen shots make scenes disjointed, almost comical. The narration is grating, especially when one knows that Welles’s version didn’t have it, and wouldn’t have needed it. The score is atrocious, and like the music of The Stranger, it makes one long for Bernard Hermann. And the editing leaves scenes feeling rushed and incomplete. The Lady from Shanghai is a film whose individually Wellesian moments leave one in awe at what the man could do, and how much he’d changed since Citizen Kane. The violence done to it by Harry Cohn, Viola Lawrence, and Heinz Roemheld, however, leaves one regretting the lost, potential masterpiece.

Notes

1. There is much debate as to the origins of the project. Welles told a story throughout his life that he grabbed the book off a shelf randomly, and asked Cohn to bail out his failing production of Around the World if Welles made him a movie. According to Castle, however, he gave Welles his own treatment of the novel, which Castle had tried, unsuccessfully, to sell to Columbia. Castle was then called into the Columbia offices to be assigned as associate producer to Welles’s version, unbeknownst to Castle that Welles had successfully sold the project in September 1945. Welles’s friend Fletcher Markle, however, claims that he and Castle helped Welles with the script in the spring of 1946, and also during location shooting in Acapulco later that fall. My initial account is a minor attempt to coalesce all versions of these stories. For more, see This is Orson Welles, pp. 508-9.

2. In fact, Stylus Magazine’s Paolo Cabrelli makes a convincing case for the scene, a view I shared even before I knew of its being against Welles’s intentions.

3. IMDb says that Joseph Walker, Frank Capra’s cameraman, did some uncredited work, but I haven’t been able to verify the claim. If I were to speculate, I would guess that he lensed some of the studio re-takes in March 1947.

4. Lederer, twistedly enough, was the nephew of Marion Davies, who in turn was William Randolph Hearst’s mistress. Lederer also married Welles’s first ex-wife, Virginia. As Simon Callow puts it, “[Welles’s daughter] Christopher accordingly spent occasional weekends in San Simeon under the roof of the man who had done everything in his power to destroy her father and his precocious masterpiece [Citizen Kane]” (Simon Callow, Orson Welles: Hello Americans, 2006, p. 222).

5. James Naremore saw a version of The Lady from Shanghai in Frankfurt, Germany in 1981 that contained slightly different editing, alternate takes of some scenes, and shots that don’t exist in the U.S. version at all. It is a mystery if this version has ever been seen outside of Europe, or if it will ever be released anywhere else.

Works Cited

–Welles, Orson & Bogdanovich, Peter. This is Orson Welles. Ed. Jonathan Rosenbaum. 1st ed. New York: HarperCollins, 1992.

–Callow, Simon. Orson Welles: Hello Americans. New York: Viking, 2006.

–Naremore, James. The Magic World of Orson Welles. 2nd ed. Dallas, TX: Southern Methodist University Press, 1989.

–Rosenbaum, Jonathan. Discovering Orson Welles. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007.