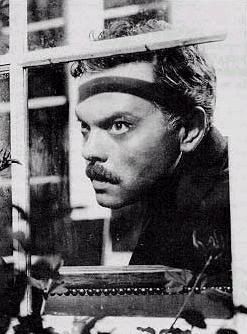

REFLECTIONS ON ORSON WELLES, PART I: AN INVENTORY

It is no secret among my friends and family that my favorite movie of all time is Orson Welles’s debut, Citizen Kane. I even wrote an 11-page paper for my high school American history class about the making of that film. What shocked my friend Igor a year-and-a-half ago was that I had seen only two of Welles’s ten completed films that are available in the U.S. (he completed thirteen in his lifetime, but three are only accessible in Europe). Shouldn’t this man be a kindred spirit, the filmmaker in whom I see myself most clearly? This is only partially true. It is because of that very description–and some of my former misconceptions about Welles and his work–that I compulsively avoided exploring all the other things he did for the next 40 years. Citizen Kane, to my mind, is just about perfect, and because of my knowledge about the studio backstabbings that destroyed It’s All True and The Magnificent Ambersons, which then led to the strife of making Othello, I thought it best to let Welles live as he should have lived, as the greatest American filmmaker of all time.

That does the man little service, however. After the controversy of Kane, RKO Pictures, in conjunction with Nelson Rockefeller, sent Welles to Brazil to make a documentary that would counteract potential fascist spheres of influence in South America. Welles sculpted It’s All True as a loving elegy to a culture that the Brazilian government was attempting to exterminate, the jangadeiros (fishermen) of the Fortaleza region. Of course, this didn’t wash with either President Vargas or RKO, and they stole Ambersons away from him, re-cutting and re-shooting much of what he’d done. (Welles had had to negotiate away his right to final cut in order to make It’s All True on the schedule that both he and RKO demanded.) What’s more, they demolished It’s All True, allowing the Brazilian bureaucracies to destroy much of what he’d shot, and never let Welles edit what was saved. RKO began a propaganda campaign against him in the U.S., declaring that he was a party-loving playboy who indulged in every excess at the expense of the “poor studio.” According to their logic, they were justified in snuffing out this “boy genius” who dared challenge their working methods.

It would be four years before Welles could make another film, a quickie thriller called The Stranger. He made it to prove to Hollywood that he was “bankable,” but that didn’t stop them from re-cutting the film behind his back; the same went for the next film he made the following year, The Lady from Shanghai. Ambersons, The Stranger and Shanghai represent, to my knowledge, the most sustained period of a studio not only re-cutting a director’s films, but destroying the footage they slashed, thus leaving the future public unable to ever see how Welles had actually intended these works to look, sound, and feel. After making a cheap version of Macbeth for Republic Pictures–and cutting out twenty minutes at the studio’s request–Welles left the U.S. for Europe, not to return until 1957.

Welles’s versions of his 1950's films–Othello and Mr. Arkadin in Europe, Touch of Evil in the U.S.–all met with venerable setbacks. It took Welles three years to film Othello because he kept running out of money, and had to act in others’ movies in order to begin shooting again. Mr. Arkadin was hacked to pieces by its producer after Welles missed editing deadlines, and currently exists in as many as six circulating versions, none of which are Welles’s final cut. Touch of Evil was gutted by more than half-an-hour and severely re-edited, so much so that Welles wrote a 58-page memo to Universal Studios with a long list of changes he believed were necessary. (Editor Walter Murch and producer Rick Schmidlin used this memo as a guideline to reconstructing the film, and that version is what’s available on DVD. Neither Welles’s original cut nor the studio’s original release version can be seen.)

Beginning in 1962 with his adaptation of Kafka’s The Trial, Welles reasserted his ability to gain final cut over his films. Unfortunately, he met with a plethora of financing problems, unable to begin or finish other projects swimming inside his head. Welles only finished five films between 1962 and his death in 1985, hardly the output he had desired.

There were seven major works that Welles started and was unable to finish in the last thirty years of his life, primarily to due to financial or legal difficulties:

The Merchant of Venice (1969)

The Deep (based on Dead Calm by Charles Williams, 1968-1973)

Don Quixote (based on Cervantes’s novel, 1955-1973)

The Other Side of the Wind (1970-1976)

Filming The Trial (1981)

The Dreamers (based on “The Dreamers” and “Echoes” by Isak Dinesen, 1978-1985)

The Magic Show (1969-1985)

Only scraps of The Dreamers and The Magic Show have survived. The Deep, The Other Side of the Wind and Filming The Trial were all but finished; however, money always got (and continues to get) in the way of their completion. The Merchant of Venice was completely finished, a 40-minute adaptation intended as part of a Welles anthology T.V. series. Before it was ever screened, two work print reels and the soundtrack were stolen and have never been recovered.

From what I understand, only Don Quixote may not have been meant to see the light of day. Filmed on and off for twenty years, it existed in as many as four different forms before star Akim Tamiroff died in 1972, and the money ran out again. Scholar Jonathan Rosenbaum has speculated that the film was “Welles’s ultimate plaything,” something he loved to kick around when he wasn’t occupied with other projects.

In addition to Welles’s unfinished films, there are at least three scripts of major significance in his body of work that never got past pre-production: Heart of Darkness (written in 1940 as his first idea for a movie, which RKO rejected), The Big Brass Ring (a political thriller written between 1981 and 1982) and The Cradle Will Rock (an autobiopic written in 1984 about Welles’s work in late 1930's socialist theater). Countless other ideas, notes and scripts exist that have never seen publication, along with an extensive body of television shows produced in Europe and the U.S.

What are we to make of Welles’s now-exceedingly messy career? One is faced with a choice: hold onto the notion that what must be evaluated is completed work, ignoring all else, or begin to incorporate the idea that unfinished product may reflect more about Welles in terms of process, and is thus just as important. If we are to embrace the former, then only three films can be seen correctly, and before a couple of years ago, only one was widely available in the U.S.:

Citizen Kane (1941) [Released on DVD through Warner Home Video, 2001.]

Chimes at Midnight (1966) [Easily accessible as a region-free import DVD.]

F for Fake (1974) [Released on DVD through Criterion Collection, 2005.]

One other film exists in Welles’s original cut and has never been tampered with–Filming Othello–but it is unavailable on home video in any country.

Should we decide to expand our horizons a little bit more, the following films are widely available, but often exist in versions not corresponding to Welles’s original intentions:

Macbeth (1948) [There is a French DVD box set that contains both of Welles’s cuts, thankfully.]

Othello (1952) [The version most easily found on DVD is a botched “restoration” from 1992.]

The Trial (1962) [Only public domain copies exist, many of which use truncated cuts.]

The Immortal Story (1968) [The only available version is a truncated Italian import DVD.]

The next level of interest would be to incorporate Welles’s work that was tampered with before it was ever released, thus making his original vision impossible to see. The vast majority of the films on this list are, sadly, all of the ones he made in Hollywood (barring Kane, of course), and thus the Welles films most readily available in the U.S.:

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) [Released on VHS.]

The Stranger (1946) [Released on various public domain DVD’s.]

The Lady from Shanghai (1948) [Released on DVD through Columbia Home Video.]

Mr. Arkadin (1955) [Three versions released as a DVD box set through Criterion.]

Touch of Evil (1958) [Reconstructed version released on DVD through Universal Home Video.]

Of course, Welles’s eight major unfinished films can’t be viewed by we average Americans, only read about; the same goes for his three major unproduced scripts, as their published versions have gone out of print. Over the next few months, I intend to view as many of the 11 completed Welles films to which I have ready access. I hope to begin a series in this blog that will explore just what the hell the work of Orson Welles really means, and if viewing them as completed works is really the way to make sense of a man who delighted in confounding expectations. Also forthcoming is an in-depth conversation with the book which helped begin this new understanding of Welles, Jonathan Rosenbaum’s recently published Discovering Orson Welles. I hope to discover, as Rosenbaum and other scholars sympathetic to his positions have assured me, that Orson Welles really was more than just Citizen Kane.

1 comment:

Thanks for sharing men excellent post I really like it, those movies always teach us everything, the bad thing is just us just learn the bad part.

Thanks, nice post.

Post a Comment