THE SNOWMAN (Raymond Briggs/Dianne Jackson, 1982)

One settles in to watch this short as a lighthearted holiday short, a 26-minute piece of children's fluff which will allow parents a moment of respite from the squalor that is the anticipation of Christmas. But The Snowman is not so ordinary. Its animation is coarse and rough-hewn, imitative of Raymond Brigg's illustrative style in his eponymous book. It's pantomimed, the music taking on a Prokofiev-like character. All of this is certainly intriguing, but in the grand picture, these qualities do not set it apart all that drastically.

What makes The Snowman one of the most (if not the most) devastating children's films ever is composer Howard Blake's central theme, used in three strategic locations: over the opening credits, the middle sequence when the boy and the snowman are flying over the northern hemisphere, and the closing credits. The film's first shot--a man walks across a barren clearing, narrating about a particularly snowy day in his childhood, and then melts into an animated crane shot over a snowy landscape--is bleak, but alluring. The music haunts and engages, but does not overpower; it merely suggests. In the middle sequence, a boy sings the song "Walking in the Air" as flight over the world marks the first transformative steps of the boy into adulthood. The theme is now rapturous, full of passion and possibility.

But the circle of the boy's mature awakening comes to a close in the final moments, when the boy leaves his house the next morning to see the snowman. What he discovers, however, is but a pile of snow and tattered clothing. He has witnessed death first-hand; he is no longer a child. Jackson doesn't leave any room for sentiment or tenderness. The film cuts away from the boy immediately after his discovery, cranes up, and fades into the all-consuming whiteness of the ground. The theme re-enters. This time, it is the harbinger of death, the melody of a heart discovering that it can be broken. Innocence is lost, experience remains. It is brutal, honest, terrifying, full of pathos, and beautiful. Death's inevitability and the loss of innocence has rarely been rendered so powerfully.

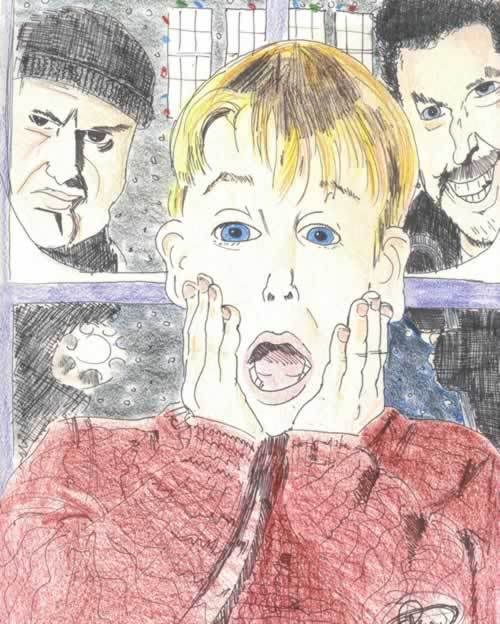

Home Alone: The Wondrous Terror of the Forbidden

What creatures haunt the inner recesses of the Child’s subconscious? Are we to believe that the agony and the ecstasy of freedom from the chains of the womb are truly one and the same? Is a freed tarantula the most poetic expression of vagina dentata the cinema has yet to produce? John Hughes and Chris Columbus dared to pose these questions, and found heart-breaking triumph in the face of Innocence itself: Macaulay Culkin.

Home Alone may be the most frightening and euphoric film about the awakening of adulthood because it refuses to shy away from manifesting those fears and joys in the external, always impressing upon us that demons lurk among us, and if one looks hard enough, you will always find them. For life is joy and terror, agony and ecstasy; the two are always coupled, and can emerge from the same source. Young Kevin McAllister, in being abandoned inside the cavern that is his suburban home, is ripped from the uterus of his overbearing mother for the first time, and must finally come to grips with life. The Munchian scream he utters while applying aftershave is his awakening of the Other in the Mirror. He goes grocery shopping; he eats ice cream for dinner; he battles criminals. All of these are fantastic expressions of the banal, symbols for Kevin’s transformation, his becoming.

And then there is Candy. O Candy, where be your gibes now, your gambols? You are the angel that awakens the transformation in the Mother, the recognition of a similar transformation, that the womb must no longer be a prison. Only then can the Mother and the Child reconcile themselves to each other. And it is the long quest, the night drive from Scranton to Chicago with the Polka Kings of the Midwest, which allows this to occur. Candy, you are Rilke’s spirit of Duino, facilitating but never participating, awakening the inner spirit but never actively engaging.

And what of the demons which emerge from the comforting shadows of police officers to be the terrors of the McMansions of suburban Chicago? Pesci and Stern are failed men, men of frustration and desperation, lashing out at the very forces which have smothered their hopes and dreams. Of course, they are the things which have emerged from Kevin’s soul, making one wonder: are these the secret manifestations of Kevin’s true fear, oppression of the spirit in the face of the modern capitalist system?

From every pore, the world of fear and displacement teems with life: the curmudgeonly Uncle Frank; the evil brother Buzz; the understanding father, the introduction of Big Pete to the rest of the world. And when what Kevin believed to be the true evil–Old Man Marley–is revealed to be his angel of awakening, then the climax of euphoria, the violent purge of the real demons, can commence. And Kevin is thus freed to rejoin Life. It never ceases to take the breath away, and electrify one with the wondrous terror of the Forbidden.

1 comment:

"The Snowman" gets me every time.

Nice blog, Davis.

Post a Comment