Iron Man (Jon Favreau)

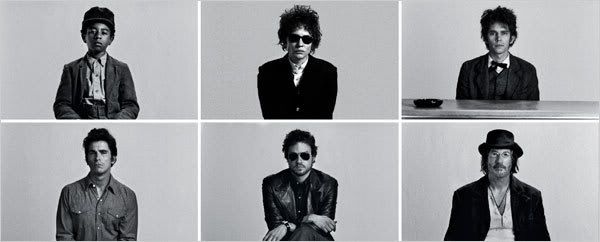

I recently had a conversation with a man who reminded me that whenever one evaluates a work of art, but especially a movie (or screenplay, which is what we were actually talking about), one always brings an “agenda” to the process of judgment. “Did this movie fit the parameters of what I expected from it? If yes, then it is good; if not, then it is bad.” This is the common mode of thought for most people when they see a movie, which is a more direct way of describing subjectivity within artistic consumption. Movie critics in general, and I in particular, all do this in one way or another. But what caused Iron Man to crystallize these thoughts is how blatantly the movie made me aware of my own agenda as I watched it.

Indeed, during the first half or so, Jon Favreau and his 4-man screenwriting team (the credited ones, anyway) do seem to want to make a layered, complex, and fun little movie. While making the first villains a bunch of vaguely ideologically defined Afghani warlords amounts to more than a bit of thoughtless Orientalism, Favreau still manages to depict Tony Stark’s (Robert Downey Jr.) transformation as a deep and personal one. One minute a too-charming weapons manufacturing billionaire, a morally awakened superhero the next, Favreau lets Downey be Downey (the man could never be boring if he tried), while still letting the pain seep through.

Even better is when Stark returns to America after 3 months in captivity in Afghanistan. He decides to improve on the prototype he built to free himself from his captors, which results in the hot-rod-red and gold titanium suit we know and love. Getting the suit built to perfection, however, involves a lot of tinkering, which leads to the funniest parts of the movie, and points to the most pointed layer that goes frustratingly unexplored.

Tony Stark’s backstory—jazzily exposited in an awards-show montage at the movie's chronological beginning—describes the man as a boy genius, graduating summa cum laude from MIT at the age of 18, and taking over his father’s weapons-manufacturing conglomerate when he is 21. Not too long after he ditches his woman-for-the-evening—a Vanity Fair reporter whose name he can’t remember—he is seen in his workshop (a funhouse of futuristic gadgets, natch) working on a car. But Favreau does something incredibly sly in that moment. Contrasted with the slick playboy image we have just witnessed, we see where Stark’s passion actually lies: in the laboratory. This is a man who loves to build things, to work out the most minute details of a complex series of problems. These moments are expanded even further when he is building the suit. After he casts off his man-about-town persona, Stark seems free to pursue his true love, and derive a massive amount of joy from it.

Around such issues is where my own “agenda” rears its ugly head. After getting these little tastes of Stark’s real character, I wanted to see the subtext expanded: I wanted Favreau to incorporate how Stark let himself—perhaps forced himself to—become a lascivious brat who cared for little else but booze, cars and women. Furthermore, the scene with Stark working on his hot-rod presents a robust opportunity for Favreau to explore how the two sides of Stark’s personality can co-exist (before he finds moral clarity, of course).

Instead, by the time the suit is finished and Stark has delivered his final speech to his assistant Pepper Potts (Gwyneth Paltrow), the moment has passed, the battle lines have been clearly drawn, and any mention of Stark’s conflicted relationship with his past has been disposed of with a couple of brief lines of dialogue. Even Stark’s initial moral imperative (use himself to destroy the weapons he inadvertently helped get into the hands of the very people he thought his weapons would destroy) vanishes in the second hour, since we see that those warlords are being controlled by Stark’s business partner, Obadiah Stane (Jeff Bridges).

Another potential for a much richer and more nuanced analysis of morality in the face of global capitalism is Stane. Bridges, like Downey, also qualifies for the “could-never-be-boring-if-(s)he-tried” category of screen actors. Despite the one-dimensional characterization that Stane eventually collapses into, Bridges still allows for him to be a bit more than a simple moustache-twirler. But when we are first introduced to him, we recognize that Stane’s bitter jealousy of Stark lies in the fact that Stane was so closely bonded to Stark the elder, and viewed the future of Stark Industries as being taken out of his hands by a young upstart whelp much smarter than himself. Throughout the first half of the movie, Stane is painted as a member of the system of the military-industrial complex run rampant, a very human but very willing member of a world which sees Afghani villagers as little more than collateral damage. Because of Bridge’s subtle performance and Favreau’s initial light touch, we understand that a man who helps create modern evil can still be a human being.

Things run off the rails when it comes to light that Stane was the one who hired the Afghani terror group to kill Stark. After subduing their leader and stealing the plans and prototype of Stark’s suit of iron, he plans on building his own suit, toward ends never actually defined. This of course leads to the big blazing shoot-out that results in Stark’s near-destruction and Stane’s total destruction. Everybody lives happily ever after.

Time after time, Favreau leaves key moral questions hanging. (The problem of their being initially raised and then discarded has stuck with me more than with the laughably stupid climax, because, well, it’s laughably stupid, and can be brushed off as such.) Dana Stevens in Slate offers up a particularly glaring example. (Full disclosure: I had read the following excerpt before I had seen the movie.)

“In one scene, the Iron Man confronts a group of Afghan villagers, unable to distinguish the civilians from the combatants. At once a Terminator-style readout appears on the inside of his mask, clearly labeling each civilian, and with surgical precision, he takes out all the bad guys, leaving the grateful good guys standing. It's a clever and viscerally satisfying gag that got a round of applause at the screening I attended—but it left me with a bitter aftertaste that lasted for the rest of the movie. How much collateral damage have we inflicted by trusting just such 'smart' weapons to make moral decisions for their users?”

I was admonished for yelling “what the fuck?!” when this scene occurred. While I may be looking through a glass darkly at it, I believe that there is enough dropping of the ball by Favreau & co. throughout the movie to let Stevens’s reading hold up. There is so much potential for making ambiguous the confluence of modern warfare and global capitalism within Iron Man that it is hard to forgive Favreau's simplistic renderings of Stark’s moral dilemmas.

I haven’t even focused my attention on the moronic metal-lite score, or the shockingly stupid dialogue uttered by Stark and Potts during the climactic battle, or the cheeky ending that leaves us wanting more. Favreau and his screenwriters do leave us wanting more; it’s just not the “more” that they think. My friend Noah—along with A.O. Scott—argued that the movie set out to fulfill the formula of the big action-superhero movie, and for him, it did that. Iron Man met his agenda, and I wish it had met mine.

EPILOGUE: When I first saw the trailer for Iron Man, the primary musical piece used was one of the greatest shit-kicking, foot-stomping songs of all time: “Iron Man,” by Black Sabbath. This song’s concluding instrumental passages find their way into the beginning of the closing credits, but I thought to myself how fascinating it might have been if Favreau had woven the song throughout the film, like Robert Altman does with the central theme of The Long Goodbye. Brilliant covers by the Bad Plus, Sir Mix-a-Lot, The Cardigans, and The Replacements are ready for service, perhaps on Stark’s car radio, or the gentle muzak of an elevator shaft . . . shit, there goes my damn agenda gettin’ in the way again.