13 Lakes (James Benning)

James Benning’s films are not for everyone. I warned my then-girlfriend what she was getting herself into if she came to see Benning’s latest with me, and though she stayed the whole time, I could’ve sworn I heard some gentle snoring coming from her direction (just kidding). Quite simply, 13 Lakes consists of thirteen 10-minute shots that never move or change perspective. Each shot is of a different lake in the U.S. Sound like background noise? Perhaps. But like the great structuralist films of the past, the nature of the cinematic experience is essential to finding the joys in the film; it forces one to really look at and listen to the image, until a whole wealth of rich variation becomes evident. Nature becomes otherworldly. (And by the way, the other part of this diptych, Ten Skies, is a Jerry Bruckheimer film by comparison.)

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik)

It is common historical knowledge that Jesse James was shot in the back of the head by the man he had once called a friend, and that said "friend," Robert Ford, achieved minor celebrity for the killing. To most, including James’s family, Ford was a sniveling little coward who deserved the killing he himself received ten years later. That general information being taken care of before the movie even starts is a sign that Andrew Dominik is after something different than the standard Western-betrayal narrative. His film is a lyrical invocation of the mythological West already being constructed in James’s lifetime, and about James himself. Sensuous slow-motion, hands running through wheat, a hauntingly backlit silhouette of James (Brad Pitt) stalking railroad tracks–this is where myth and brutal fact collide. Pitt’s James is a saintly madman, in love with and mocking of his own celebrity. As Ford, Casey Affleck embodies a young obsessive who despises himself and James for that obsession. And as evidence of the first major case of American celebrity mythology, James intrinsically recognizes that he needs Ford as much as Ford needs him. The History Channel-like voiceover serves as a sharp counterpoint to the dreamy and violent imagery, literalizing factual history while Dominik paints it as glorious madness. And when James sets his guns down one April morning in order to dust a picture on his living room wall, he closes his eyes, and quietly awaits the only thing that can save him: annihilation.

Lake of Fire (Tony Kaye)

As an employee at Film Forum, one of the major art houses in New York City, I take it very personally that Tony Kaye’s latest film–which Film Forum premiered last October–played for only nine days to abysmally small crowds, when it was intended to last weeks. The film met a similar fate in major cities all over the country, and never escaped urban centers. It is a tragedy that people did not have the open mind to discover the fascinating and terrifying glories of Kaye’s years-in-the-making epic. The most astonishing thing about Lake of Fire is its sober evenhandedness, not daring to collapse into morally unambiguous ideology the way that the abortion debate so often does. Shot in luminous 35mm black-and-white, Kaye sketches out events in the history of abortion in the 1990s & 2000s, interviews major players on both sides of the issue, and refuses to give any easy answers. Eventually, after you see two abortions performed in front of your eyes, you realize that life, not only in its creation but also how it is lived after it is created (i.e. the autonomy women should have over their own bodies), is too easily destroyed by what certain men and women demand, based on the "word of God."

No Country for Old Men (Joel & Ethan Coen)

The thing that makes No Country for Old Men a masterpiece is the creation of an apocalyptic universe right in the middle of southwest Texas. Everything that happens–from Llewellyn Moss’s (Josh Brolin) theft of $2 million found in the desert, to the pursuit by hired killer Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), to Sheriff Ed Tom Bell’s (Tommy Lee Jones) instinctive deduction of events–happens with a force of purpose that is hardly ever explained. We simply see incredibly specific, methodic, minute actions, always with intention behind them. We just don’t know their secrets. Instead, we see details, hear sounds, and feel reactions that create a complete universe, one where a demon physically stalks the earth. But even he isn’t born of Hell, for he is a mortal. Shifting perspectives are expertly crafted, with subjectivities kept intact. The barren wilderness is both liberating and oppressive, as is the almost complete absence of non-diegetic sound. Even the ending, with its eery anti-climaxes on all fronts, is appropriate. In this universe, nobody is satisfied, not even this mortal demon. And as Ed Tom Bell sits at his breakfast table and recounts a comforting dream of his father being a protecting force in his life, he has no choice but to wake up.

Regular Lovers (Philippe Garrel)

Philippe Garrel’s love letter to his youth and his stern rebuttal to Bernardo Bertolucci’s facile The Dreamers, Regular Lovers is a haunting portrait of the aftermath of May ’68. Shot in sumptuous but also charmingly tossed-off black and white, Garrel’s chamber epic follows a young poet, Francois (Louis Garrel, the director’s son and also one of the stars of The Dreamers), as he negotiates how to exist after his and his friends’ moment of triumph evaporates. Regular Lovers is intoxicated by the quotidian, the casual atmosphere of young people unsure of where to go or what to do. It also does not demonize all figures of authority, nor does it sanctify the behavior of Francois and his friends. (The scene where some cops enter Francois and his friend’s apartment is hilarious in the way the cops admire the art on the walls.) The centerpiece, a communal dance to The Kinks’ “This Time Tomorrow,” is a gorgeously rapturous and melancholy ode to trying to establish a community in a world that has rejected you.

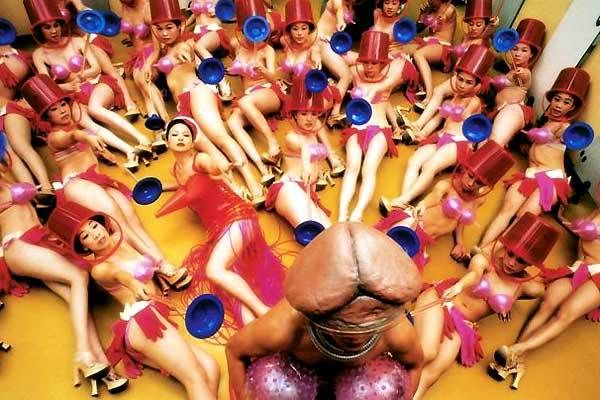

The Wayward Cloud (Tsai Ming-liang)

In a certain respect, The Wayward Cloud should be the happy ending the protagonists of What Time is it There? never received. After years of separation and spiritual longing, they are indeed reunited. Tsai’s gifts for rendering the absurdly erotic are on full display here, mostly involving a drought, random bursts into garish musical numbers, and many, many watermelons. Raw sensuality drips from every frame. And perhaps the film’s tragic, sexually violent ending proves that the two lovers’ romance was always little more than a dream, an ethereal fantasy which only proves brutal if ever made real.

Zodiac (David Fincher)

There is clearly an intelligence behind the David Fincher of Alien3, Se7en, and Fight Club, less so behind The Game and Panic Room. But, with Zodiac, Fincher has delivered his second Great Work, and his first true epic. Like great Hollywood art, the film is dense, uncompromising, and somewhat avant-garde while hewing all of these tendencies to a popular, mainstream framework. We disappear down a rabbit’s hole of facts, both hard and soft, and at the end of the day, cannot decipher what justice or knowledge are supposed to mean.

In many respects, Zodiac is the opposite side of the same coin as Fincher's breakthrough, Se7en. Both are serial killer procedurals, but whereas Se7en was all philosophical doom, Zodiac plunges into a labyrinth of quotidian details, adding up to something and nothing at the exact same time. Facts overlap, contradict each other, converge and split apart, until no matter how long you've been staring at them, they refuse to bring you any closer to unmasking the man who murdered five people between 1969 and 1970 in northern California. Police are able to generate a rough sketch of what he looks like, but in one letter, he says he wears a disguise. He seems to be psychotic, but always sounds calm. Moreover, he ceases to kill for no apparent reason--hardly the standard reaction for a psychotic murderer. Three men commit themselves so deeply to the case that it ultimately wrecks them: for Jake Gyllenhaal's cartoonist, his marriage disintegrates. For Robert Downey Jr.'s reporter, he crawls to the bottom of a bottle and loses his job. For Mark Ruffalo's cop, he nearly puts away a man he is convinced is guilty, but can't prove. Questions of obsession, the media, and the potentially inherent falsity of facts leaves us with nothing to grasp onto, which is exactly how Fincher wants to leave us.

Tomorrow, the beginning of the end! The 4 best movies of 2007, presented with their own individual posts, in alphabetical order.

3 comments:

It is certainly interesting for me to read this article. Thank author for it. I like such themes and anything connected to them. I would like to read a bit more soon.

Rather nice place you've got here. Thank you for it. I like such topics and anything connected to them. BTW, try to add some images :).

Those are a good movies I have to say it, but this kind of movies just teach us how to kill each other..

Thanks for sharing.

Post a Comment