Even though I consider this film on equal footing with the other 3 mentioned in this section, I should mention that in this year's Film Comment Critics' Poll, I voted this film to be the very best of the year. Take that for what you will.

I'm Not There and The Grand Symphonic Dance of Chaos, Clocks, and Watermelons

"How long it had been, I couldn’t even say.

The day I arrived looks a lot like today.

At least, that’s how it seemed at the time."

Todd Haynes’s masterpiece, like its very subject, is everything and nothing to everyone and nobody. It is a poem, a concerto, an essay, and a doctoral dissertation. It is also only a movie. It is a rapturous celebration of the freedom of the artist and a devastating critique of the human consequences of such freedom. It is a canny exploration of the political realities of the 60s, and a philosophical reconstruction of identity. It is not really about Bob Dylan, and completely about "Bob Dylan." It is coldly academic and passionately emotional, incredibly dense, and delightfully effervescent. It is, along with There Will Be Blood, the best American film of 2007.

Some already well-reported talking points to cover about I’m Not There, but which are nonetheless important to consider when tackling the film’s many long and winding roads:

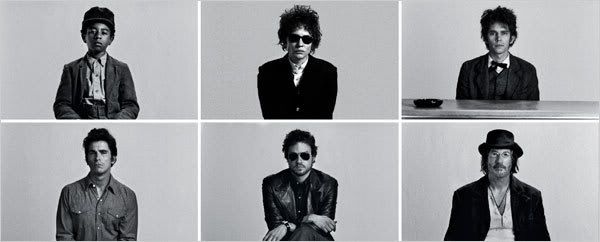

–Bob Dylan is played by six different people (Marcus Carl Franklin, Ben Whishaw, Christian Bale, Heath Ledger, Cate Blanchett, Richard Gere), each portraying Dylan in a different phase of his life.

–None of these six characters diegetically interact with each other.

–None of these six characters are played by people whose race, gender, nationality, and/or age correspond to the Dylan they are portraying.

–None of these six characters are named Bob Dylan.

Now that we’ve gotten that out of the way, we can begin parsing just what the hell is going on in this whirling dervish of a film.

Bob Dylan is a cultural figure who has seemed impervious, especially in his heyday (1962-1977), to the poison of celebrity. The more controversy he courted, the more legendary he became. He has existed within and without of the temporal moment, whereas Elvis Presley and The Beatles have been practically defined by it. The more people attempt to define him, the more he seems to slip through our fingers.

Haynes manages to effortlessly capture this mobility, presenting Dylan not as one man, but four men, a boy, and a woman. While the film’s structural spine progresses from Dylan-as-Guthrie (Franklin) to Dylan-as-folk-hero (Bale) to Dylan-as-rock-god (Blanchett) to Dylan-as-recluse (Gere), these various parts dance around each other, moving back and forth across time, and eventually, space. This is not to mention how Dylan-as-Rimbaud (Whishaw) and Dylan-as-damaged-family-man (Ledger) weave their way across the whole story.

Since Dylan is not a fixed entity who can be linearly and psychologically understood, Haynes approaches him as a construction, one invented by the American public, but also by Dylan himself. His earliest avatar is an 11-year-old African-American boy named Woody Guthrie. In 1959, Woody has escaped from a child correctional facility in Minnesota and has jumped the rails, planning on making it big as a folk singer. He believes himself to be Guthrie, while inventing his biography on the spot. Then, Arthur Rimbaud appears, a 19-year-old poet being interrogated by a nameless tribunal in a nondescript government office. He proceeds to dance in and out of the film, offering mad aphorisms about nature and creativity. Back to Woody: when he is confronted about living 25 years in the past, we cut to a documentary about the troubled life of Jack Rollins, legendary folk singer of Greenwich Village who disappeared from the limelight in early 1964.

We jump back to Woody’s journeyman story, and when he is tossed into a river off of a boxcar, we move to the story of Robbie Clark, an actor who became famous for playing Rollins in a hit movie from 1964. His marriage is falling apart, and to that end, the perspective taken is predominantly not Clark’s, but his wife Claire’s (Charlotte Gainsbourg). We again double back to Woody, until he makes his final escape to visit the real Woody Guthrie in a New Jersey hospital. He vanishes from the story, only to be replaced by Jude Quinn, who literally guns down an "unappreciative" audience at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival.

The rest of the film revolves around this central figure, until we meet Billy, the aged outlaw who escaped Pat Garrett’s bullet and went into hiding in a bizarre small town in Missouri. After this introduction, all four remaining narratives slowly build their way to a firm break, until Jack finds God and becomes John (perhaps a seventh Dylan incarnation), Robbie gets divorced and drives off with his kids to go on a boat trip, Jude OD’s and then fatally crashes his motorcycle, and Billy escapes from prison and rides a boxcar out of town.

While this might feel like a thorough synopsis, it only touches on what Haynes accomplishes by a radical collection of distancing effects and identifying techniques, all at the same time. Dylan’s lyrics, verbatim excerpts from various interviews, and quotes from other films saturate the dialogue. Visual passages from 8 ½, Masculin Feminin, Eat the Document and Don’t Look Back are quoted wholesale. This is a film of cultural pastiche, which is only appropriate. If it appears to lack coherence, that is because attempting to dissect a life necessarily lends itself to incoherence, and no life could be better described as incoherent than Bob Dylan’s. These techniques—and the absence of any firm notion of story or character—provide a lens of analysis on the whole proceedings, studying Dylan like so many others have studied him. But now, we have a set of tools that reveals just how constructed previous studies have been. And no better technique is the splintering of Dylan into six people.

The way we have traditionally understood Dylan is in very concrete biographical elements, all closed off from the others. Haynes exploits this by his fractured narrative. But he goes one step further to reveal that such an understanding is ludicrous, because Dylan is only one man, and these six personalities live in him all at once, and have from the very beginning. If Woody disappears near the beginning of the film, it is because he is the first to become completely integrated into the greater whole. By 1962, Dylan had digested his influences and emerged as his own being. Casting Franklin emphasizes not only the roots of his influences, but the apprentice-like quality of Dylan at that time, ready from the beginning to be someone completely different. Haynes’s "natural Brechtianism," as J. Hoberman calls it, intrinsically understands what analytical tendencies would arise in someone seeing a young black child who calls himself Woody Guthrie, but also living under the pretext of "Bob Dylan."

Similarly, Haynes captures the strange behavioral implosions that Dylan showed the world from late 1965 to mid-1966 in Cate Blanchett’s performance as Jude Quinn. The most physically radical of all of Haynes’s Dylan avatars, Blanchett organically assumes the image of Dylan, which by the mid-60s was as familiar to the public as he was ever likely to become. But instead of Jamie Foxx-style mimicry, Blanchett becomes something totally different, a Dylan that is being invented right before our eyes. By becoming a man-woman (or is it a woman-man?), Quinn is never allowed to be fixed in our minds, constantly forcing us to reconsider what Dylan’s image at that time actually meant.

When it comes to Jack Rollins, we are given the least amount of conventional concrete evidence of a character, as the story is presented as a television documentary attempting to discover what ever happened to the legendary folk singer. But if considered through this Brechtian window, we see that Haynes once again demands that we think about this phase of Dylan’s life as that most fetishized by mainstream popular culture. Indeed, much of the documentary parodies the lost idealism of the folk generation, how they became commodities, and how Dylan himself first became a commodity. Rollins’s rigidity in not only his music and politics but also in how he violently bites the hand that feeds him is echoed in the rigid and obnoxious form of the TV documentary. Sheer comic magic comes from Alice Fabian (Julianne Moore), the Joan Baez figure full of pomp and circumstance, who also milks the phony "naturalism" of the medium for cathartic laughs.

Many people think that Robbie Clark is the most conventional and least interesting of these six narratives, but Haynes manages to subtly reveal another temporal warp in how Dylan the Family Man has been exhibited and received. It is the only story to not be told chronologically, which in itself implies that this Dylan infects all the others more deeply. And as another distancing layer, the story is told from Claire’s eyes. (Plunging down the rabbit hole even further, much of the expository information is recited in third-person voiceover by Robbie himself.) Haynes’s move is to show that when we think of Dylan in Woodstock raising a family, or succumbing to the more damning elements of fame, sympathy drifts to Suze Rotolo (Dylan’s girlfriend during the early folk years) and his first wife, Sara. The moment when love dies is when Robbie attempts to inhabit Jack Rollins. He is incapable of discovering the quality that defines Dylan’s allure, and Claire realizes that the man with whom she is in love is an apparition, a construction onto which she cannot grasp. Robbie embraces only what Rollins can superficially give him, but decays at the prospect of liberating himself from those gifts.

Billy is easily the most hated part of I’m Not There by most of its detractors, and even by some of its supporters. A good friend adamantly declared that "it just doesn’t work." Others similarly claim that it feels too out-of-place, too abstract, and too un-Dylan to fit in with the rest of the ghosts that haunt the film’s spaces. The character of Billy, however, is the key to the whole project, the avatar that unifies the other figures into a temporally malleable meditation on Dylan as a whole. Billy lives in a town called Riddle, MO, a name that doesn’t leave much to the imagination. It is crucial to note that Woody, at the beginning of this, told a couple of hobos that he had spent a great deal of time in Riddle. Billy tells his story in voiceover, about how in Riddle, he is invisible, allowed to live out his remaining years. But Pat Garrett has returned, announcing plans to demolish Riddle to allow a superhighway to run through the valley.

Time has already begun to bend, as Billy looks out over a valley to see Vietnamese villages being carpet-bombed. Garrett and company arrive in Buicks. Billy, after protesting Garrett’s actions, is taken to jail in such a vehicle. But everything else about the place suggests rural America in the late 19th Century. This would also be impossible if Billy actually is whom he says, because his age would place the action at around 1919 or so. And in the film’s final temporal kink, Billy, upon escaping prison and hopping the boxcar, discovers a beat-up old guitar in one of the bunks: it is Woody’s. These six Dylans have now been completely absorbed together, able to be viewed as connected elements in a naturally disconnected man, who can call upon any number of these elements to present himself to the rest of the world.

J. Hoberman, in one of the best pieces of criticism on I’m Not There, says that the film "is an essay that derives its intellectual force from the idea of Bob Dylan, and its emotional depth from his songs." The truth of this statement is unshakeable, and is one of the keys to realizing that Haynes’s film isn’t merely a cold, analytical, postmodern study. None of Dylan’s hits are diegetically present: there is no use of "Blowin’ in the Wind," "A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall," "Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right," "Only a Pawn in Their Game," "It Ain’t Me Babe," "Subterranean Homesick Blues," "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35," "Lay Lady Lay," "Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door," "Tangled Up in Blue," or "Hurricane." "The Times They Are A-Changin’" makes a brief appearance, but it’s Jack Rollins singing an excerpt on a Steve Allen-style talk show. (Jack’s singing duties ae taken up by Mason Jennings.) "All Along the Wachtower" is heard fleetingly, and is performed in the Hendrix mode by Eddie Vedder. "Like a Rolling Stone" kicks open the back doors of your mind only over the closing credits, and "Mr. Tambourine Man" is ripped apart in the last moments of the film by Dylan’s wailing harmonica solo from a 1966 live performance.

The brunt of the musical work is done by the more obscure, and perhaps more personal, songs of the Dylan catalogue. The only Dylan that ultimately matters is the one who emerges within these songs, and a dialogue between the music and the film is immediately begun. What’s more, covers find their way in as well, suggesting that even Dylan himself might not matter at all; all that’s left is the music he has allowed us to appropriate for ourselves.

A key example of Haynes’s intelligence in creating such a dialogue is the scene in which Claire announces that she is leaving Robbie. What builds to a fight quickly collapses into one last moment of sexual—and emotional—intimacy between the two. As they embrace, "Idiot Wind" fades into the soundtrack, but it’s not the version found on Blood on the Tracks. Instead, it is an earlier version he recorded when he initially laid down the songs in New York in the fall of 1974. It’s rougher, in a lower key, and achingly sparse, only Dylan’s voice and his acoustic guitar breathing the song into life. The lyrics, once a scathing indictment of a former love’s inability to stay true to herself, becomes an elegiac and mournful loss of something that, despite the singer’s best efforts to destroy, will live on as tender memory. It is a perfect echo of the last moments Robbie and Claire will share, and when it cuts to the divorce being finalized in court, the music and lyrics’ contrapuntal dance only becomes more incisive as we see Robbie losing his temper in the parking lot.

The other centerpiece is one of the greatest and least-heralded songs Dylan ever made, "Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands." The final song from his mid-60s opus, Blonde on Blonde (an album more prevalent in I’m Not There than any other, interestingly enough), Haynes deploys it over Jude Quinn’s motorcycle crash and his final soliloquy, which he may be reciting from beyond the grave. The speech is from an acerbic interview Dylan gave to Nat Hentoff in a 1966 issue of Playboy, but from the mouth of Blanchett, along with the instrumental sections of the song playing beneath her words, it feels like a final eulogy to the transitory nature of Dylan’s life and music. Indeed, his final words, "everyone knows I’m not a folk singer," are followed by a swell in the music, a coy half-smile directly into the camera, and six gunshots firing at each Dylan’s mug shot (an echo from the beginning of the film).

I have seen I’m Not There four times, and have only begun to scratch the surface with this paltry amalgam of thoughts. It is a deep, rich, and constantly revelatory film, one which sees Dylan as one and many beings, instantly recognizable but hardly knowable. It is a call to thinking about time and identity in completely fresh and exciting ways. It is the American cousin to Syndromes and a Century in its celebration of temporal, artistic, and existential freedom. Like both Bob Dylan and, as it turns out, "Bob Dylan," it’s not there, but it is willing to see where it might go.

Like Bob Dylan, "Bob Dylan," and I'm Not There, criticism of the film is in a constant state of becoming. Here are six pieces which all helped bring this one into existence:

J. Hoberman in The Village Voice

Larry Gross in Film Comment

Kent Jones in The Nation

Jonathan Rosenbaum in The Chicago Reader

An anonymous blogger's rant about the film and Dylan's life

Jacob Rubin in The New Republic

Since Dylan is not a fixed entity who can be linearly and psychologically understood, Haynes approaches him as a construction, one invented by the American public, but also by Dylan himself. His earliest avatar is an 11-year-old African-American boy named Woody Guthrie. In 1959, Woody has escaped from a child correctional facility in Minnesota and has jumped the rails, planning on making it big as a folk singer. He believes himself to be Guthrie, while inventing his biography on the spot. Then, Arthur Rimbaud appears, a 19-year-old poet being interrogated by a nameless tribunal in a nondescript government office. He proceeds to dance in and out of the film, offering mad aphorisms about nature and creativity. Back to Woody: when he is confronted about living 25 years in the past, we cut to a documentary about the troubled life of Jack Rollins, legendary folk singer of Greenwich Village who disappeared from the limelight in early 1964.

We jump back to Woody’s journeyman story, and when he is tossed into a river off of a boxcar, we move to the story of Robbie Clark, an actor who became famous for playing Rollins in a hit movie from 1964. His marriage is falling apart, and to that end, the perspective taken is predominantly not Clark’s, but his wife Claire’s (Charlotte Gainsbourg). We again double back to Woody, until he makes his final escape to visit the real Woody Guthrie in a New Jersey hospital. He vanishes from the story, only to be replaced by Jude Quinn, who literally guns down an "unappreciative" audience at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival.

The rest of the film revolves around this central figure, until we meet Billy, the aged outlaw who escaped Pat Garrett’s bullet and went into hiding in a bizarre small town in Missouri. After this introduction, all four remaining narratives slowly build their way to a firm break, until Jack finds God and becomes John (perhaps a seventh Dylan incarnation), Robbie gets divorced and drives off with his kids to go on a boat trip, Jude OD’s and then fatally crashes his motorcycle, and Billy escapes from prison and rides a boxcar out of town.

While this might feel like a thorough synopsis, it only touches on what Haynes accomplishes by a radical collection of distancing effects and identifying techniques, all at the same time. Dylan’s lyrics, verbatim excerpts from various interviews, and quotes from other films saturate the dialogue. Visual passages from 8 ½, Masculin Feminin, Eat the Document and Don’t Look Back are quoted wholesale. This is a film of cultural pastiche, which is only appropriate. If it appears to lack coherence, that is because attempting to dissect a life necessarily lends itself to incoherence, and no life could be better described as incoherent than Bob Dylan’s. These techniques—and the absence of any firm notion of story or character—provide a lens of analysis on the whole proceedings, studying Dylan like so many others have studied him. But now, we have a set of tools that reveals just how constructed previous studies have been. And no better technique is the splintering of Dylan into six people.

The way we have traditionally understood Dylan is in very concrete biographical elements, all closed off from the others. Haynes exploits this by his fractured narrative. But he goes one step further to reveal that such an understanding is ludicrous, because Dylan is only one man, and these six personalities live in him all at once, and have from the very beginning. If Woody disappears near the beginning of the film, it is because he is the first to become completely integrated into the greater whole. By 1962, Dylan had digested his influences and emerged as his own being. Casting Franklin emphasizes not only the roots of his influences, but the apprentice-like quality of Dylan at that time, ready from the beginning to be someone completely different. Haynes’s "natural Brechtianism," as J. Hoberman calls it, intrinsically understands what analytical tendencies would arise in someone seeing a young black child who calls himself Woody Guthrie, but also living under the pretext of "Bob Dylan."

Similarly, Haynes captures the strange behavioral implosions that Dylan showed the world from late 1965 to mid-1966 in Cate Blanchett’s performance as Jude Quinn. The most physically radical of all of Haynes’s Dylan avatars, Blanchett organically assumes the image of Dylan, which by the mid-60s was as familiar to the public as he was ever likely to become. But instead of Jamie Foxx-style mimicry, Blanchett becomes something totally different, a Dylan that is being invented right before our eyes. By becoming a man-woman (or is it a woman-man?), Quinn is never allowed to be fixed in our minds, constantly forcing us to reconsider what Dylan’s image at that time actually meant.

When it comes to Jack Rollins, we are given the least amount of conventional concrete evidence of a character, as the story is presented as a television documentary attempting to discover what ever happened to the legendary folk singer. But if considered through this Brechtian window, we see that Haynes once again demands that we think about this phase of Dylan’s life as that most fetishized by mainstream popular culture. Indeed, much of the documentary parodies the lost idealism of the folk generation, how they became commodities, and how Dylan himself first became a commodity. Rollins’s rigidity in not only his music and politics but also in how he violently bites the hand that feeds him is echoed in the rigid and obnoxious form of the TV documentary. Sheer comic magic comes from Alice Fabian (Julianne Moore), the Joan Baez figure full of pomp and circumstance, who also milks the phony "naturalism" of the medium for cathartic laughs.

Many people think that Robbie Clark is the most conventional and least interesting of these six narratives, but Haynes manages to subtly reveal another temporal warp in how Dylan the Family Man has been exhibited and received. It is the only story to not be told chronologically, which in itself implies that this Dylan infects all the others more deeply. And as another distancing layer, the story is told from Claire’s eyes. (Plunging down the rabbit hole even further, much of the expository information is recited in third-person voiceover by Robbie himself.) Haynes’s move is to show that when we think of Dylan in Woodstock raising a family, or succumbing to the more damning elements of fame, sympathy drifts to Suze Rotolo (Dylan’s girlfriend during the early folk years) and his first wife, Sara. The moment when love dies is when Robbie attempts to inhabit Jack Rollins. He is incapable of discovering the quality that defines Dylan’s allure, and Claire realizes that the man with whom she is in love is an apparition, a construction onto which she cannot grasp. Robbie embraces only what Rollins can superficially give him, but decays at the prospect of liberating himself from those gifts.

Billy is easily the most hated part of I’m Not There by most of its detractors, and even by some of its supporters. A good friend adamantly declared that "it just doesn’t work." Others similarly claim that it feels too out-of-place, too abstract, and too un-Dylan to fit in with the rest of the ghosts that haunt the film’s spaces. The character of Billy, however, is the key to the whole project, the avatar that unifies the other figures into a temporally malleable meditation on Dylan as a whole. Billy lives in a town called Riddle, MO, a name that doesn’t leave much to the imagination. It is crucial to note that Woody, at the beginning of this, told a couple of hobos that he had spent a great deal of time in Riddle. Billy tells his story in voiceover, about how in Riddle, he is invisible, allowed to live out his remaining years. But Pat Garrett has returned, announcing plans to demolish Riddle to allow a superhighway to run through the valley.

Time has already begun to bend, as Billy looks out over a valley to see Vietnamese villages being carpet-bombed. Garrett and company arrive in Buicks. Billy, after protesting Garrett’s actions, is taken to jail in such a vehicle. But everything else about the place suggests rural America in the late 19th Century. This would also be impossible if Billy actually is whom he says, because his age would place the action at around 1919 or so. And in the film’s final temporal kink, Billy, upon escaping prison and hopping the boxcar, discovers a beat-up old guitar in one of the bunks: it is Woody’s. These six Dylans have now been completely absorbed together, able to be viewed as connected elements in a naturally disconnected man, who can call upon any number of these elements to present himself to the rest of the world.

J. Hoberman, in one of the best pieces of criticism on I’m Not There, says that the film "is an essay that derives its intellectual force from the idea of Bob Dylan, and its emotional depth from his songs." The truth of this statement is unshakeable, and is one of the keys to realizing that Haynes’s film isn’t merely a cold, analytical, postmodern study. None of Dylan’s hits are diegetically present: there is no use of "Blowin’ in the Wind," "A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall," "Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right," "Only a Pawn in Their Game," "It Ain’t Me Babe," "Subterranean Homesick Blues," "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35," "Lay Lady Lay," "Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door," "Tangled Up in Blue," or "Hurricane." "The Times They Are A-Changin’" makes a brief appearance, but it’s Jack Rollins singing an excerpt on a Steve Allen-style talk show. (Jack’s singing duties ae taken up by Mason Jennings.) "All Along the Wachtower" is heard fleetingly, and is performed in the Hendrix mode by Eddie Vedder. "Like a Rolling Stone" kicks open the back doors of your mind only over the closing credits, and "Mr. Tambourine Man" is ripped apart in the last moments of the film by Dylan’s wailing harmonica solo from a 1966 live performance.

The brunt of the musical work is done by the more obscure, and perhaps more personal, songs of the Dylan catalogue. The only Dylan that ultimately matters is the one who emerges within these songs, and a dialogue between the music and the film is immediately begun. What’s more, covers find their way in as well, suggesting that even Dylan himself might not matter at all; all that’s left is the music he has allowed us to appropriate for ourselves.

A key example of Haynes’s intelligence in creating such a dialogue is the scene in which Claire announces that she is leaving Robbie. What builds to a fight quickly collapses into one last moment of sexual—and emotional—intimacy between the two. As they embrace, "Idiot Wind" fades into the soundtrack, but it’s not the version found on Blood on the Tracks. Instead, it is an earlier version he recorded when he initially laid down the songs in New York in the fall of 1974. It’s rougher, in a lower key, and achingly sparse, only Dylan’s voice and his acoustic guitar breathing the song into life. The lyrics, once a scathing indictment of a former love’s inability to stay true to herself, becomes an elegiac and mournful loss of something that, despite the singer’s best efforts to destroy, will live on as tender memory. It is a perfect echo of the last moments Robbie and Claire will share, and when it cuts to the divorce being finalized in court, the music and lyrics’ contrapuntal dance only becomes more incisive as we see Robbie losing his temper in the parking lot.

The other centerpiece is one of the greatest and least-heralded songs Dylan ever made, "Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands." The final song from his mid-60s opus, Blonde on Blonde (an album more prevalent in I’m Not There than any other, interestingly enough), Haynes deploys it over Jude Quinn’s motorcycle crash and his final soliloquy, which he may be reciting from beyond the grave. The speech is from an acerbic interview Dylan gave to Nat Hentoff in a 1966 issue of Playboy, but from the mouth of Blanchett, along with the instrumental sections of the song playing beneath her words, it feels like a final eulogy to the transitory nature of Dylan’s life and music. Indeed, his final words, "everyone knows I’m not a folk singer," are followed by a swell in the music, a coy half-smile directly into the camera, and six gunshots firing at each Dylan’s mug shot (an echo from the beginning of the film).

I have seen I’m Not There four times, and have only begun to scratch the surface with this paltry amalgam of thoughts. It is a deep, rich, and constantly revelatory film, one which sees Dylan as one and many beings, instantly recognizable but hardly knowable. It is a call to thinking about time and identity in completely fresh and exciting ways. It is the American cousin to Syndromes and a Century in its celebration of temporal, artistic, and existential freedom. Like both Bob Dylan and, as it turns out, "Bob Dylan," it’s not there, but it is willing to see where it might go.

Like Bob Dylan, "Bob Dylan," and I'm Not There, criticism of the film is in a constant state of becoming. Here are six pieces which all helped bring this one into existence:

J. Hoberman in The Village Voice

Larry Gross in Film Comment

Kent Jones in The Nation

Jonathan Rosenbaum in The Chicago Reader

An anonymous blogger's rant about the film and Dylan's life

Jacob Rubin in The New Republic

1 comment:

Very nice analysis. Nice bibliography, too.

And if you dug the film (I think you did) then I know you'll enjoy my new novel, BLOOD ON THE TRACKS.

It's a murder-mystery. But not just any rock superstar is knocking on heaven's door. The murdered rock legend is none other than Bob Dorian, an enigmatic, obtuse, inscrutable, well, you get the picture...

Suspects? Tons of them. The only problem is they're all characters in Bob's songs.

You can get a copy on Amazon.com or go "behind the tracks" at www.bloodonthetracksnovel.com to learn more about the book.

Post a Comment